Artificial intelligence is rapidly permeating every aspect of the investment process, and due diligence is no exception. We are seeing a growing number of new tools and platforms that promise to automate or dramatically accelerate diligence using AI. The critical question is not whether this is possible, but whether it is actually desirable.

At Rockies Venture Club, we have spent years conducting due diligence the traditional way—through disciplined, human-led diligence teams evaluating hundreds of companies. Some of our most consequential diligence discoveries did not come from spreadsheets or checklists, but from intuition-driven follow-ups: checking patent conflicts, Secretary of State filings, or other secondary sources that uncovered material misrepresentations. In retrospect, AI likely could have identified many of those issues more quickly and more systematically.

That said, I have long believed that effective due diligence is as much about psychology as it is about finance, markets, or technology. We routinely encounter founders who do not think ambitiously enough, or who are evasive about exit strategy because, consciously or not, they are seeking investors to buy them a job rather than to build a scalable, realizable business. We evaluate how deeply founders have researched their markets, how rigorously they have modeled expenses and revenues, how thoughtfully they have designed go-to-market and channel strategies, and how realistically they have planned team growth. These elements reveal how founders think—often more clearly than the data itself—and this is an area where AI alone remains limited.

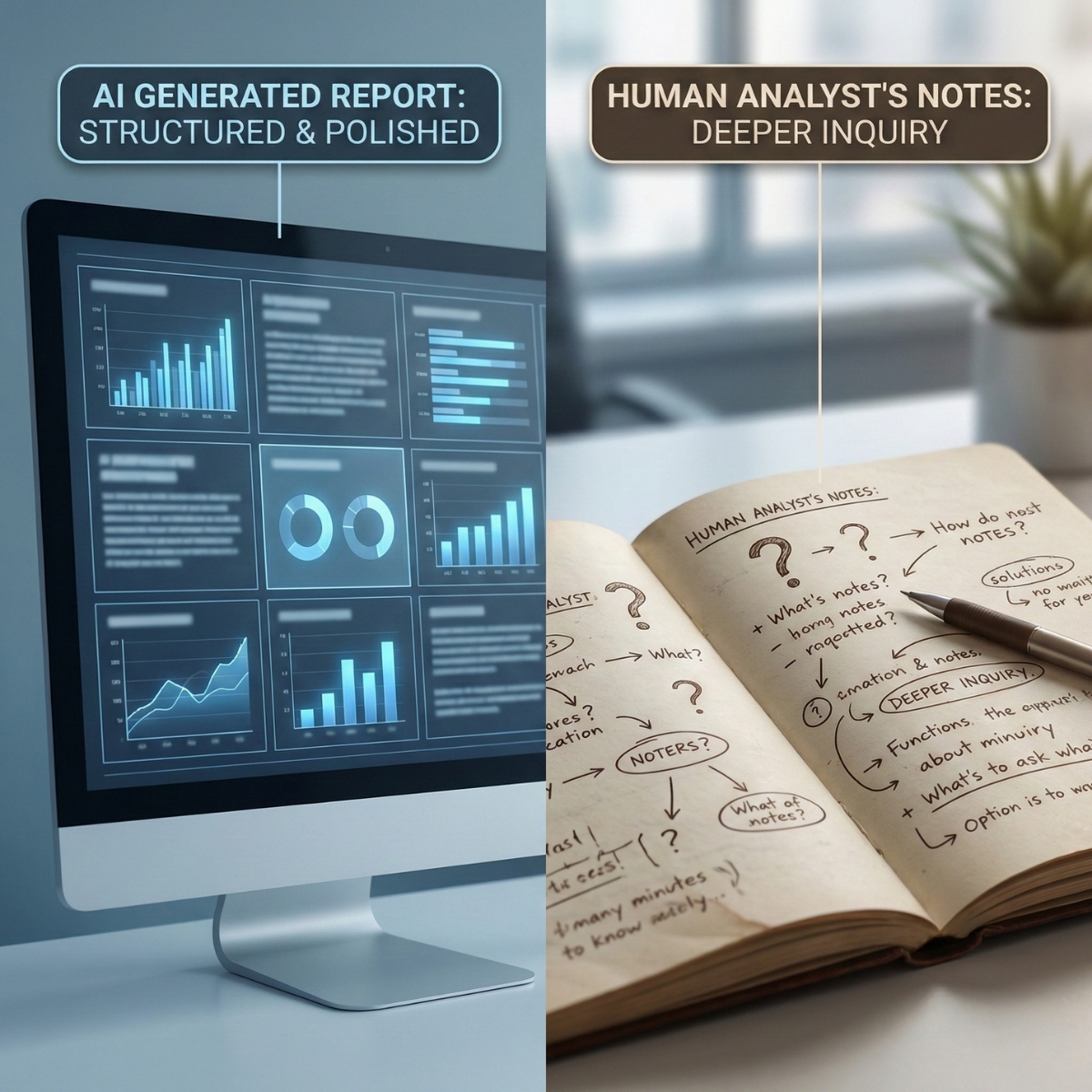

The temptation to rely heavily on AI for diligence is strong. Over the past six months, we have experimented with a variety of AI-driven approaches to compare outcomes against our labor-intensive traditional process. At first glance, the workflow appears compelling: upload a pitch deck and data room, run a few prompts, and receive a polished output. What we consistently found, however, was something I would describe as an “analyst report.” It looks comprehensive and checks the expected boxes, but it rarely asks the hardest questions or surfaces the core issues that truly determine investment risk.

In our traditional diligence process, we begin with a strategic kickoff meeting to guide the diligence team. Given that the potential scope of inquiry for any investment is effectively infinite, the purpose of this meeting is to identify the most critical risks and priority areas for investigation. While the team reviews all ten diligence categories, it goes particularly deep on those key risk areas. Developing that focus requires what I half-jokingly call “manual AI”: carefully reviewing the deck, financial models, operating plans, and supporting documents before forming a view on the deal’s true strengths and weaknesses.

Our current approach to AI-assisted diligence follows the same principle. First, do the homework. Then identify the key risks. Only after that do we bring AI into the process. From there, we apply the “Five Whys” technique—continuously asking follow-up questions based on each response we receive from AI. This method has proven highly revealing.

As an example, I once asked ChatGPT whether venture capital investments lose money in nine out of ten deals. It initially responded affirmatively. Knowing that this “nine out of ten” statistic is a widely repeated but misleading trope, I pushed further and asked for the original source material and scholarly research supporting the claim. The revised answer was that venture capitalists lose money on approximately 5.5 out of 10 deals—a materially different conclusion. This illustrates why iterative questioning is essential. Without it, AI can easily reinforce pre-existing assumptions embedded in the prompt rather than challenge them.

I am particularly impressed with the work of Alexander Gregorian, who now leads our due diligence teams following in the footsteps of Kevin Kudra who has led our due diligence efforts for many years. Alexander’s mandate is intentionally not to “do due diligence,” but to foster a culture of inquiry and deep research across the teams. The initial diligence drafts under this approach have been strong, and I am optimistic about how this model will continue to evolve. Our goal is to produce diligence that is genuinely useful to both angel and venture investors—and, equally important, to the companies we choose to back.

.jpg)